DERMIS

אוצרת: שיר ויזל 25.2.23 -1.4.2023

links

טקסט בעברית

interview by Yonatan Mishal, Benedicta Magazin

Portfolio Magazin

time out

Fade to Grey, 2015, Installation view, Raw Art Gallery, Photography: Youval Hai

Fade to Grey

January 22 - February 28, 2015

Curator: Nogah Davidson

Raw Art Gallery is pleased to announce "Fade to Grey", a solo exhibition by Revital Rettig. This is her first show with the gallery presented in Tel Aviv.

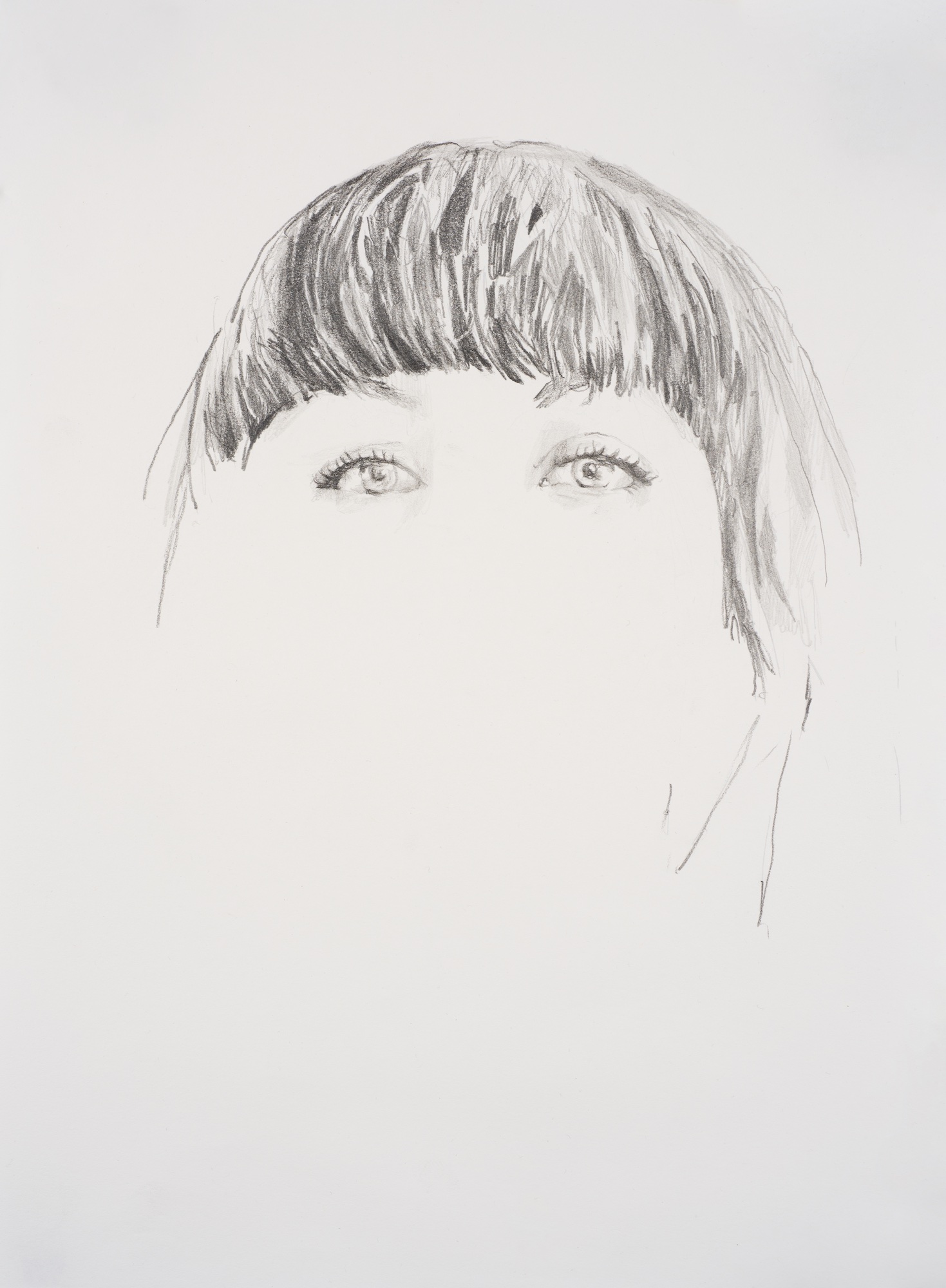

It is no secret that the general public has little appreciation for contemporary art and people that may be educated, intelligent and culture enthusiasts, respond reluctantly when introduced to contemporary art. Presumably there are a number of reasons accountable for this chilly reception, but it seems that the most dominant problem is related to the issue of technical artistic skills. When a painting, a drawing or a sculpture does not explicitly demonstrate artisanal virtuosity, the common criticism argues that contemporary art is no more than the emperor's new clothes: not art but rather a fraud, a joke on the viewer's expense under the false pretense of intellectualization, or as the saying goes: "a child could have made that." Revital Rettig's exhibition addresses this matter, as her works seemingly range between abstract, free-handed scribbles and realistic, meticulously detailed academic techniques.

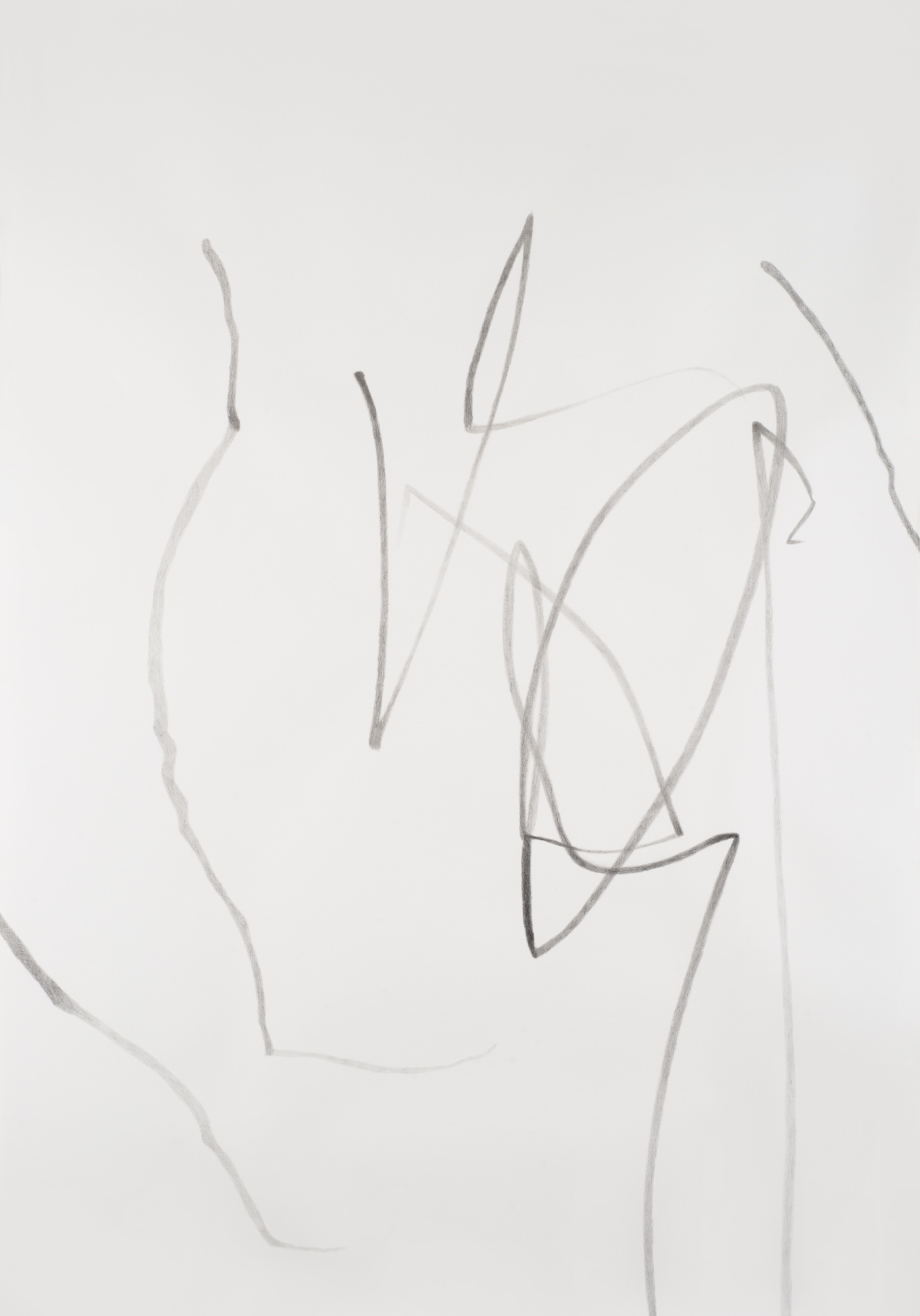

Set between these two extremes is a series in which the artist recreates her infant daughter's first scribbles. Naturally her daughter had no intention of expressing or representing anything other than what the drawings are– a reflection of her enjoyment and interest at the moment in time which they were executed. Though every child enjoys drawing or scribbling, sadly this basic pleasure is often terminated at a young age by self censorship and/ or social censorship. It can be said that adult people who still create art, have managed to keep to some extent the (perhaps childish) freedom to engage in a practice that brings them joy. Even if they may also occasionally struggle with the paralyzing fear brought on by the white canvas/ paper.

Thus, when we encounter a child drawing non-judgmentally, without any need for the drawing to be beautiful or to even make sense, when the drawing demonstrates his/ her freedom to explore, to imagine and to enjoy, we can't help being in awe of the natural wisdom in which he/ she experiences life and wonder why this basic knowledge escapes us in our adult life. Why is it that in order to rid our minds of disturbing thoughts and experience joy as adult s we need drugs, alcohol, month long silent retreats, fifteen year long psychological treatments.

And so perhaps the saying "a child could have made that" is not as negative as it may seem. Perhaps instead of seeing it as a delegitimizing insult, it can rather be regarded as an aspiration. That said, we must distinguish between Rettig's work and the Naïve or "outsider" art genres: though she too finds beauty in the elemental intuitions of childhood, her perspective is disillusioned for she realizes the hopelessness of her aspirations. Her strictly executed reiteration of her daughter's random lines represents the disparity between the two – whilst the daughter is motivated by freedom of expression; the mother is motivated by her contemplations on the freedom that is no more. She understands she can never return to a time free of self doubt.

This is also evident in another abstract series in which she created clusters of dense lines. Though we see in these works Rettig part from the ascetic, precise line and present coarser strokes, there is still a significant difference between the daughter's loose, lightweight gestures and the way the mother fills the paper with a dark accumulated mass. Whereas the daughter's lines are light and airy, the mother's have an emotional baggage that almost threatens to tear the paper. As if there were not enough graphite in the world to satisfy the emotional relief she is seeking.

In contrast, when Rettig recreates her daughter's lines, her own lines are so gentle you could hardly see any pencil traces, the texture is smooth and completely uniform. Here we see her display a traditionally realistic drawing method: created through extended periods of observation and hard work, aimed to deliver an accurate portrayal of the original object. Originally a couple of centimeters long, her daughters scribbles were painstakingly enlarged to the smallest details, imitating with varied shades and thicknesses the different amounts of pressure her daughter put on the markers.

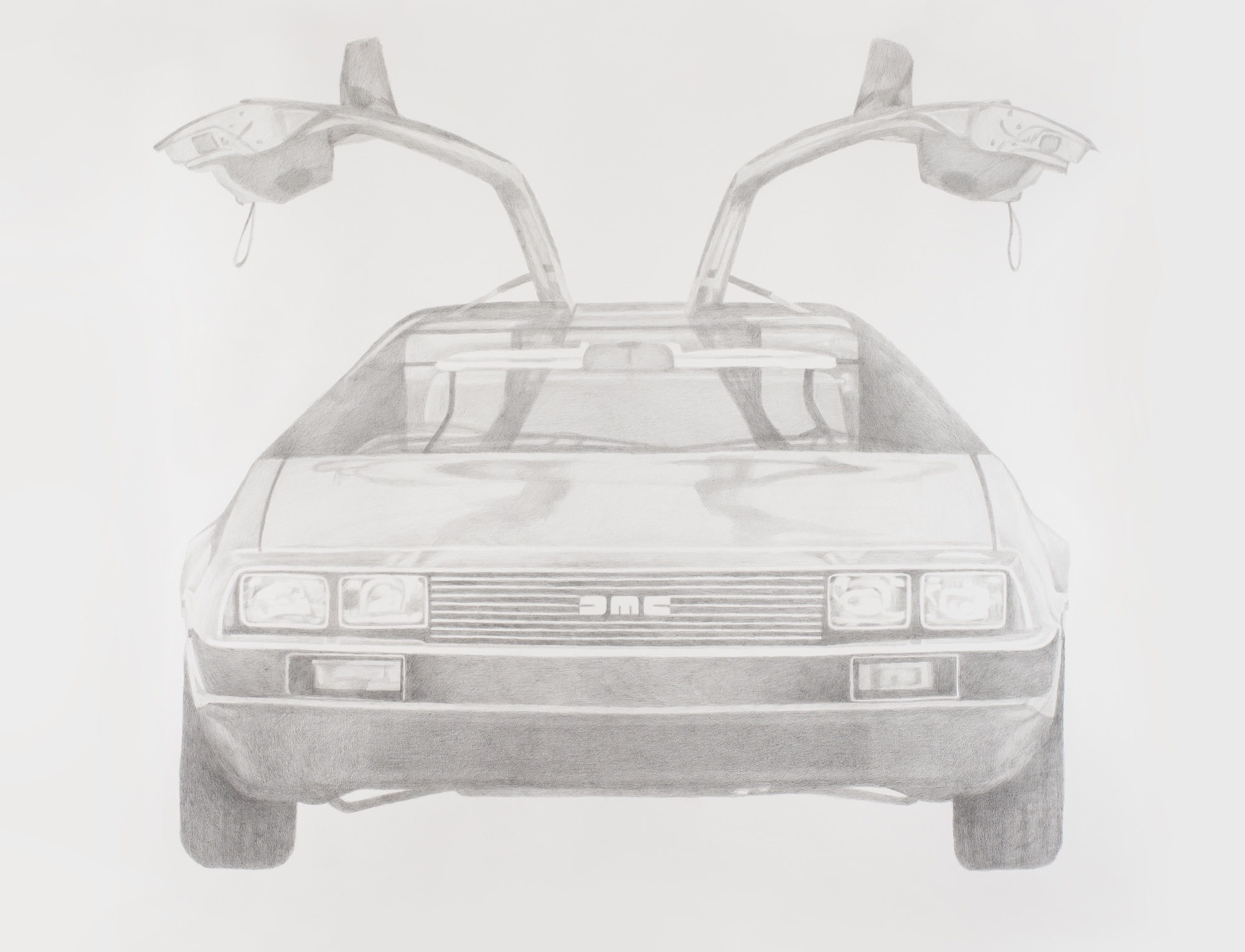

This is a prevalent method in her realistic drawings: a supposedly low and unvalued subject matter, created in a fastidious academic drawing technique. Rettig often plants a cynical layer which undermines the seriousness of the artistic action. Aware of the absurd severity this kind of artistic endeavor requires: she can work 20 hours on an accurate drawing of the Delorean, the car from the "Back to the Future" movies; amusingly draw a package of colored markers as a range of gradient shades of grey; or create a unique piece of Warhol's banana from the Velvet Underground's album cover –a work originally intended for mass distribution so the original is needless, illogical.

There are many illogical aspects to artistic practice: the artist may dwell over the tiniest details in his studio (which seem crucial at the time), only for them to be ignored completely, misunderstood or simply unnoticed later by the viewers. Given there is an audience at all, since contemporary art spaces have few visitors most hours of the day, it makes one wonder if the efforts are justified. Even so the art world is still surrounded by a glorified aura, with its artifacts framed and showcased in polished white spaces, alongside long and convoluted texts that analyze its meaning.

Rettig is well aware of this: she shifts between high and low, grave efforts and thoughtlessness, intentions and coincidence, tradition and individualism. The variety she displays in the exhibition clarifies that she constantly tests the limits of her own borders, tries out every possibility out there so as to find her place in each and every one of them. Like the package of colored markers in one of her works, Rettig's research is about transitions, about the spectrum – the range of possibilities that lie between two poles.

Nogah Davidson, January 2015

Links

טקסט בעברית︎

A recommendation by Smadar Sheffi on Galatz (radio show), 9.2.15

A recommendation by Yonatan Mishal, Benedicta Magazine

THE SOLO

PROJECT

Bassel, switzerland

curator : Nogah Davidson

Revital Rettig creates installations combining different drawing methods with drawing based new media works . The delicate world that Rettig creates gives the viewer an entry into a very private world. As though the viewer were taking a glance into a personal diary or secret sketchbook that has come to life. As her works are all derived from her own and her families' memories and stories, the process of re-documentation creates a subversive interpretation of memories and their preservation.

It may be said this personal diary is depicted within different artistic subjects. For example, it discusses the philosophy of the photograph through drawing. As her works are usually based on studies of

photographs, one may find different kinds of pictures. Going from family portraits, to "passport" photos; to pictures of small scenarios- a brother and sister walking in the garden, her husband laying back on the sofa (looking like he is watching television); to pictures of friends doing "funny faces" to the camera or just hanging around – pictures of the sort people post on social networks, showing their day-to-day life.

Alongside to the latter, there are drawings of objects which symbolize too, different fragments from the artists' biography – a Lithuanian money bill (a fragment of her family's history) a pile of rubbish bags, a plant and so on. Another theme in her works seems to break from her personal biography, mostly typified by animals- such as dogs, jellyfish, owls, crocodiles, etc`. These two themes (of objects and animals) reaffirm that Rettig deals with her memories and personal story, through a process folded inside grand themes of art history and critique. Thus Still Life, Portraiture, the Frozen and the Moving image, the Decisive Moment- all come together under Rettig's private filter.

However, this filter is not homogeneous- as she creates her imagery in different drawing styles and techniques. Going from painstaking detail to loose, expressive gestures filled with movement and body; from traditional to digital drawing, to animation. More so, the temperament that comes through from the works goes from a macabre – comedic style of interpretation to melancholia, to a distanced, so called objective standpoint.

If so, the combination of these different styles, languages and methods, seems to formulate the artist's memories in an inner hierarchy and measures of emotional weight that these memories possess. Like a series of disconnected imagery, floating before one's eyes before going to sleep, some are full of detail, some translucent, almost there but not quite.

June 2012